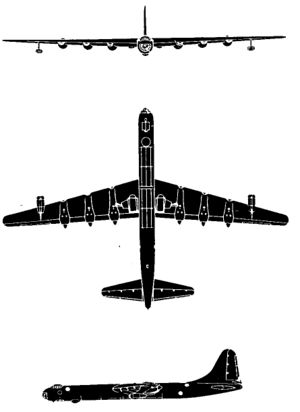

Convair B-36

| B-36 "Peacemaker" | |

|---|---|

|

|

| The B-36D used both piston and jet engines. | |

| Role | Strategic bomber |

| Manufacturer | Consolidated Vultee |

| Designed by | Ted Hall |

| First flight | 8 August 1946 |

| Introduced | 1949 |

| Retired | 12 February 1959 |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 384 |

| Unit cost | US$4.1 million (B-36D)[1] |

| Variants | Convair YB-60 Convair XC-99 Convair X-6 (Unbuilt) |

The Convair B-36 "Peacemaker"[N 1]was a strategic bomber built by Convair and operated solely by the United States Air Force (USAF) from 1949 to 1959. The B-36 was the largest mass-produced piston engine aircraft ever made. It had the longest wingspan of any combat aircraft ever built (230 ft or 70 m), although there have been larger military transports. The B-36 was the first bomber capable of delivering nuclear weapons that fit inside the bomb bay without aircraft modifications. With a range greater than 6,000 mi (9,700 km) and a maximum payload of 72,000 lb (33,000 kg), the B-36 was the first operational bomber with an intercontinental range. This set the standard for subsequent USAF long range bombers, such as the B-47 Stratojet, B-52 Stratofortress, B-1 Lancer, and B-2 Spirit.

Contents |

Development

The genesis of the B-36 can be traced to early 1941, prior to the entry of the U.S. into World War II. At the time it appeared there was a very real chance that Britain might fall to the Nazi 'Blitz', making a strategic bombing effort by the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) against Germany impossible with the aircraft of the time.[3] The U.S. would need a new class of bomber that could reach Europe from bases in North America,[4] necessitating a combat range of at least 5,700 miles (9,200 km), the length of a Gander, Newfoundland–Berlin round trip. The USAAC therefore sought a bomber of truly intercontinental range.[5][6]

The USAAC opened up a design competition for the very long-range bomber on 11 April 1941, asking for a 450 mph (720 km/h) top speed, a 275 mph (443 km/h) cruising speed, a service ceiling of 45,000 ft (14,000 m), beyond the range of ground-based anti-aircraft fire, and a maximum range of 12,000 miles (19,000 km) at 25,000 ft (7,600 m).[7] These proved too demanding—far exceeding the technology of the day—for any short-term design,[5] so on 19 August 1941 they were reduced to a maximum range of 10,000 mi (16,000 km), an effective combat radius of 4,000 mi (6,400 km) with a 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) bombload, a cruising speed between 240 and 300 mph (390 and 480 km/h), and a service ceiling of 40,000 ft (12,000 m).[4]

Experimentals and prototypes

Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation (later Convair) and Boeing Aircraft Company took part in the competition, with Consolidated winning a tender on 16 October 1941. Consolidated asked for a $15 million contract with $800,000 for research and development, mock-up, and tooling. Two experimental bombers were proposed, the first to be delivered in 30 months, and the second within another six months. originally designated Model B-35, the name was changed to B-36 to avoid confusion with the Northrop YB-35.[5][8]

Throughout its development, the B-36 would encounter various delays. When the United States entered World War II on 7 December 1941, Consolidated was ordered to slow down the B-36 project and increase production of the B-24 Liberator. The first mockup was inspected on 20 July 1942, following six months of refinements. A month after the mockup inspection the project was moved from San Diego, California to Fort Worth, Texas, which set back development several months. Consolidated changed the tail from a twin-tail to a single, thereby saving 3,850 pounds, but this change would delay delivery by 120 days. The tricycle landing gear system would allow the B-36 to land at only three airports in the United States (Fort Worth, Eglin Field, Florida, and Fairfield-Suisun Field (now Travis AFB) in California[9]), therefore Consolidated designed a four-wheel truck-type gear, which distributed the weight more evenly and reduced weight by 1,500 lb.[5][10][11] Changes in the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) requirements would add back any weight saved in redesigns, and cost more time. A new antenna system needed to be designed to accommodate an ordered radio and radar system. The Pratt & Whitney engines were redesigned, adding another 1,000 lb.[12]

World War II and after

Early in the war, the military refused to supply materials, tradespeople, and engineers to the project, which slowed work. As the Pacific war progressed, the United States increasingly needed a bomber capable of reaching Japan from its bases in Hawaii, and the B-36 began its development in earnest again. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, in discussions with high ranking officers of the AAF, decided to waive normal Army procurement procedures, and on 23 July 1943 ordered 100 B-36s before the completion and testing of the two prototypes.[11] The first delivery was due in August 1945, and the last in October 1946, but Consolidated (now renamed Convair) delayed delivery. The aircraft was unveiled on 20 August 1945, and flew for the first time on 8 August 1946.

After the Cold War began in earnest with the 1948 Berlin Airlift and the 1949 atmospheric test of the first Soviet atomic bomb, American military planners sought bombers capable of delivering the very large and heavy first-generation atomic bombs. The B-36 was the only American aircraft with the range and payload to carry such bombs from airfields on American soil to targets in the USSR. (Storing nuclear weapons in foreign countries was, and remains, diplomatically sensitive and risky).

The B-36 was arguably obsolete from the outset, being piston-powered, particularly in a world of super-sonic jet interceptors,[3][13] but its jet rival, the B-47 Stratojet, which did not become fully operational until 1953, lacked the range to attack the Soviet homeland from North America and could not carry the huge first-generation hydrogen bomb. Nor could the other American piston bombers of the day, the B-29 or B-50.[14] Intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) did not become effective deterrents until the 1960s. Until the B-52 Stratofortress became operational in the late 1950s, the B-36, as the only truly intercontinental bomber, continued to be the primary nuclear weapons delivery vehicle of the Strategic Air Command (SAC).[3]

Convair touted the B-36 as the "aluminum overcast", a so-called "long rifle" giving SAC truly global reach.[3] While General Curtis LeMay headed SAC (1949–57), he turned the B-36 arm, through intense training and development, into an effective nuclear delivery force, forming the heart of the Strategic Air Command. Its maximum payload was more than four times that of the B-29, even exceeding that of the B-52. The B-36 was slow and could not refuel in midair, but could fly missions to targets 3,400 mi (5,500 km) away and stay aloft as long as 40 hours.[3] Moreover, the B-36 was believed to have "an ace up its sleeve": a phenomenal cruising altitude for a piston-driven aircraft, made possible by its huge wing area and six 28-cylinder engines, putting it out of range of all piston fighters, early jet interceptors, and ground batteries.[3]

Operating and financial problems

Nevertheless, the B-36 was difficult to operate, prone in its early service years to catastrophic engine fires, electrical failures, and other costly malfunctions. In later years, inaccessible fuel and oil leaks were problems. To its critics, these problems made it a "billion-dollar blunder".[15] In particular, the United States Navy saw it as a costly bungle, diverting Congressional funding and interest from naval aviation and aircraft carriers in general, and carrier–based nuclear bombers in particular. In 1947, the Navy attacked Congressional funding for the B-36, alleging it failed to meet Pentagon requirements. The U.S. Navy held to the preeminence of the aircraft carrier in the Pacific during World War II, presuming carrier-based aircraft would be decisive in future wars. To this end, the Navy designed the USS United States (CVA-58), a "supercarrier" capable of launching huge fleets of tactical aircraft or nuclear bombers. It then pushed to have funding transferred from the B-36 to the USS United States. The Air Force successfully defended the B-36 project, and the United States was officially cancelled by Secretary of Defense Louis A. Johnson in a cost-cutting move. Several high-level Navy officials questioned the government's decision, alleging a conflict of interest because Johnson had once served on Convair's Board of Directors. The uproar following the cancellation of United States was nicknamed the "Revolt of the Admirals".[16]

The furor, as well as the significant use of aircraft carriers in the Korean War, resulted in the design and procurement of the subsequent Forrestal class of supercarriers, which were of comparable size to the United States but with a design geared towards greater multirole use with composite air wings of fighter, attack, reconnaissance, electronic warfare, early warning and anti-submarine warfare aircraft. At the same time, heavy manned bombers for the Strategic Air Command were also deemed crucial to national defense and, as a result, the two systems were never again in competition for the same budgetary resources.

Design

The B-36 took shape as an aircraft of immense proportions; in comparison to the large aircraft designed in the 1940s, it was two-thirds longer than the previous "superbomber", the B-29. The wingspan and tail height of the B-36 exceeded those of the Antonov An-22, the largest ever mass-produced propeller-driven aircraft.[3] Only with the advent of the Boeing 747 and the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, both designed two decades later, did aircraft capable of lifting a heavier payload become commonplace.

The wings of the B-36 were large even when compared with present-day aircraft, exceeding, for example, those of the C-5 Galaxy, and enabled the B-36 to carry enough fuel to fly very long missions without refueling. The widest point around the chord of the wing was seven and a half feet thick containing a crawlspace that allowed crew access to the engines.[17] The wing area permitted cruising altitudes well above the operating ceiling of any 1940s-era piston and jet-turbine fighters. All versions of the B-36 could cruise at over 40,000 ft (12,000 m). B-36 mission logs commonly recorded mock attacks against U.S. cities while flying at 49,000 ft. In 1954, the turrets and other nonessential equipment were removed, resulting in a "featherweight" configuration believed to have resulted in a top speed of 423 mph (700 km/h),[18] and cruise at 50,000 ft (15,000 m) and dash at over 55,000 ft (16,800 m), perhaps even higher.[19]

The large wing area and the option of starting the four jet engines gave the B-36 a wide margin between stall speed (VS) and maximum speed (Vmax) at these altitudes. This made the B-36 more maneuverable at high altitude than the USAF jet interceptors of the day, which either could not fly above 40,000 ft (12,000 m), or if they did, were likely to stall out when trying to maneuver or fire their guns.[20] However, the Navy argued that their F2H Banshee fighter could intercept the B-36, thanks to its ability to operate at more than 50,000 ft (15,000 m).[21] The Air Force declined the Navy's invitation to a fly-off between the Banshee and the B-36. Later, the new Secretary of Defense, Louis A. Johnson, who considered the U.S. Navy and Naval Aviation essentially obsolete in favor of the U.S. Air Force and Strategic Air Command, forbade putting the Navy's claim to the test.[22]

The propulsion system alone made the B-36 a very unusual aircraft. All B-36s featured six 28-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-4360 'Wasp Major' radial engines. Even though the prototype R-4360s delivered a total of 18,000 hp (13 MW), early B-36s were slow and required long takeoff runs. The situation improved with later versions delivering 3,800 hp (2.8 MW) apiece.[23] Each engine drove an immense three-bladed propeller, 19 ft (5.8 m) in diameter, mounted in the pusher configuration. This unusual configuration prevented propeller turbulence from interfering with airflow over the wing, but also led to chronic engine-overheating due to insufficient airflow around the engines, resulting in numerous in-flight engine fires.

Beginning with the B-36D, Convair added a pair of General Electric J47-19 jet engines suspended near the end of each wing; these were also retrofitted to all extant B-36Bs. Thus the B-36 came to have 10 engines ("six turnin' and four burnin' ", as said by American airmen), more than any other mass-produced aircraft. The jet pods greatly improved takeoff performance and dash speed over the target. In normal cruising flight, the jet engines were shut down to conserve fuel.

The B-36 had a crew of 15. As in the B-29, the pressurized flight deck and crew compartment were linked to the rear compartment by a pressurized tunnel through the bomb bay. In the B-36, one rode through the tunnel on a wheeled trolley, by pulling oneself on a rope. The rear compartment featured six bunks and a dining galley, and led to the tail turret.[24] The B-36 also tested the experimental Boston Camera.

The XB-36 featured a single-wheel landing gear whose tires were the largest ever manufactured up to that time, 9 ft 2 in (2.7 m) tall, 3 ft (1 m) wide, and weighing 1,320 lb (600 kg), with enough rubber for 60 automobile tires.[3] These tires placed so much weight per unit area on runways, the XB-36 was restricted to the Fort Worth airfield adjacent to the plant of manufacture, and to a mere two USAF bases beyond that. At the suggestion of General Arnold, the single-wheel gear was soon replaced by a four-wheel bogie.[25] At one point a tank-like tracked landing gear was also tried on the XB-36, but proved heavy and noisy and was quickly abandoned.[3]

Weaponry

The four bomb bays could carry up to 86,000 lb (39 metric tons) of bombs, more than 10 times the load carried by the World War II workhorse, the B-17 Flying Fortress, and substantially more than the entire B-17's gross weight.[26] The B-36 was not designed with nuclear weaponry in mind, because the mere existence of such weapons was top secret during the period when the B-36 was conceived and designed (1941–46). Nevertheless, the B-36 stepped into its nuclear delivery role immediately upon becoming operational. In all respects except speed, the B-36 could match what was arguably its approximate Soviet counterpart, the Tu-95, which began production in January 1956 and at the time of this writing is still in service.[27] Until the B-52 came on line, the B-36 was the only means of delivering the first generation Mark-17 hydrogen bomb,[28] 25 ft (7.5 m) long, 5 ft (1.5 m) in diameter, and weighing 42,000 lb (19,000 kg), the heaviest and bulkiest American aerial nuclear bomb ever. Carrying this massive weapon required merging two adjacent bomb bays.

The defensive armament consisted of six remote-controlled retractable gun turrets, and fixed tail and nose turrets. Each turret was fitted with two 20 mm cannons, for a total of 16 cannons, the greatest defensive gunnery ever carried by any aircraft. Recoil vibration from gunnery practice often caused the airplane's electrical wiring to jar loose or the vacuum tube electronics to malfunction, leading to failure of the aircraft controls and navigation equipment. This contributed to the crash of B-36B 44-92035 on 22 November 1950.[29]

The Convair B-36 was the only aircraft designed to carry the T-12 Cloudmaker, a gravity bomb weighing 43,600 lb (19,800 kg) and designed to produce an earthquake bomb effect. The first prototype XB-36 flew on 8 August 1946. The speed and range of the prototype failed to meet the standards set out by the Army Air Corps in 1941. This was expected, as the engines required (Pratt & Whitney R-4360s) were not yet available, and the lack of qualified workers and materials needed to install them prevented Convair from achieving its goals.[11][30]

A second aircraft, the YB-36, flew on 4 December 1947. It featured a redesigned high visibility bubble canopy, which was later adopted for production. Altogether, the YB-36 was much closer to the production aircraft. Additionally, the engines used on the YB-36 were a good deal more powerful and more efficient.

The first of 21 B-36As were delivered in 1948. They were admittedly interim airframes, intended for crew training and later conversion. No defensive armament was fitted as none was ready. Once later models were available, all B-36As were converted to RB-36E reconnaissance models. The first B-36 variant meant for normal operation was the B-36B, delivered beginning in November 1948. This aircraft met all the 1941 requirements, but had serious problems with engine reliability and maintenance (changing the 336 spark plugs was a task dreaded by ground crews), and with the availability of armaments and spare parts. Later models featured more powerful variants of the R-4360 engine, improved radar, and redesigned crew compartments.

The four jet engines raised fuel consumption, thus reducing range. Meanwhile, the advent of air-to-air missiles rendered conventional gun turrets obsolete. In February 1954, the USAF awarded Convair a contract reducing the weight of the entire B-36 fleet by implementing a new "Featherweight" design program in three configurations:

- Featherweight I removed the 6 movable gun turrets and other defensive hardware.

- Featherweight II removed the rear compartment crew comfort features, and all hardware accommodating the XF-85 parasite fighter.

- Featherweight III incorporated both configurations I and II.

The six turrets eliminated by Featherweight I reduced the aircraft's crew from 15 to 9. Featherweight III enabled a longer range and an operating ceiling of at least 47,000 ft (14,000 m), features especially valuable for reconnaissance missions. The B-36J-III configuration (the last 14 made) featured a single radar-aimed tail turret, extra fuel tanks in the outer wings, and landing gear allowing the maximum gross weight to rise to 410,000 lb (190,000 kg). Production of the B-36 ceased in 1954.[31]

Operational history

The B-36, including its GRB-36, RB-36, and XC-99 variants, was in service as part of the USAF Strategic Air Command from 1948 through 1959. The B-36 never dropped a bomb or fired a shot in active service.

Maintenance

The B-36 was too large to fit in most hangars. Moreover, even an aircraft with the range of the B-36 needed to be stationed as close to the enemy as possible, and this meant the northern continental United States, Alaska, and the Arctic. As a result, most "normal" maintenance, such as changing the 56 spark plugs (always at risk of fouling by the leaded fuel of the day) on each of its six engines, or replacing the dozens of bomb bay light bulbs shattered after a gunnery mission, was performed outdoors, in 100 °F (38 °C) summers or −60 °F (−51 °C) winters, depending on the location. Special shelters were built so that the maintenance crews could enjoy a modicum of protection while working on the engines. Often, ground crews were at risk of slipping and falling from icy wings, or being blown off the wings by a propeller running in reverse pitch.

The wing roots were thick enough, 7 ft (2.1 m), to enable a flight engineer to access the engines and landing gear by crawling through the wings. This was possible only at altitudes not requiring pressurization.[32]

The Wasp Major engines also had a prodigious appetite for lubricating oil, each engine requiring its own 100 gal (380 l) tank. A former ground crewman has written: "[I don't recall] an oil change interval as I think the oil consumption factor handled that." It was not unusual for a mission to end simply because one or more engines ran out of oil.

Engine fires

Much more than other large aircraft powered by piston engines, the B-36 was very prone to engine fires. This problem was exacerbated by the propellers' pusher configuration, which increased carburetor icing. The design of the R-4360 engine tacitly assumed that it would be mounted in the conventional tractor configuration—propeller/air intake/28 cylinders/carburetor—with air flowing in that order. In this configuration, the carburetor is bathed in warmed air flowing past the engine, and so is unlikely to ice up. However, the R-4360 engines in the B-36 were mounted backwards, in the pusher configuration—air intake/carburetor/28 cylinders/propeller. The carburetor was now in front of the engine and so could not benefit from engine heat, and also made more traditional short term carburetor heat systems unsuitable. Hence, when intake air was cold and humid, ice gradually obstructed the carburetor air intake, which in turn gradually increased the richness of the air/fuel mixture until the unburned fuel in the exhaust caught fire. Three engine fires of this nature led to the first loss of an American nuclear weapon, described below[33]

Crew experience

Training missions were typically in two parts; first, a 40 hour flight—followed by some time on the ground for refueling and maintenance—then a 24 hour second flight. With a sufficiently light load, the B-36 could fly at least 10,000 mi (16,000 km) nonstop, and the highest cruising speed of any version, the B-36J-III, was only 230 mph (380 km/h). Turning the jet engines on could raise the cruising speed to over 400 mph (650 km/h), but the resulting higher fuel consumption reduced the range. Hence a 40-hour mission, with the jets used only for takeoff and climbing, flew about 9,200 mi (15,000 km).

The B-36 was not a particularly enjoyable aircraft to fly. Its overall performance, in terms of speed and manuverability, was never considered sprightly. Lieutenant General James Edmundson likened it to "...sitting on your front porch and flying your house around."[34] Despite its immense exterior size, the pressurized crew compartments were relatively cramped, especially when occupied for 24 hours by a crew of 15 in full flight kit.

War missions would have been essentially one-way, taking off from forward bases in Alaska or Greenland, overflying the USSR, and landing in Europe, North Africa (Morocco), or the Middle East. Ironically, recollections of crew veterans reveal that while crews were confident of their ability to complete a mission if called upon to do so, they were less confident of surviving the weapon delivery itself.[35] Their concerns were a function of the relatively low speed of the aircraft coupled with the extreme destructive power of the bombs they were carrying, resulting in the aircraft still being within blast range once the bombs detonated on target. These concerns were borne out by the 1954 Operation Castle tests, in which B-36s flew near detonations in the 15-megaton range, at distances believed typical of wartime delivery, and experienced extensive blast damage.[36]

Experiments

The B-36 was employed in a variety of aeronautical experiments throughout its service life. Its immense size, range and payload capacity lent itself to use in research and development programs. These included nuclear propulsion studies, and "parasite" programs in which the B-36 carried smaller interceptors or reconnaissance aircraft.[37]

In May 1946, the Air Force began the Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft (NEPA) project which was followed in May 1951 by the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) program. The ANP program required that Convair modify two B-36s under the MX-1589 project. One of the modified B-36s studied shielding requirements for an airborne reactor to determine whether a nuclear aircraft was feasible. The Nuclear Test Aircraft (NTA) was a B-36H-20-CF (serial number 51-5712) that had been damaged in a tornado at Carswell AFB on 1 September 1952. This aircraft, designated the XB-36H (and later NB-36H), was modified to carry a 1 MW, air-cooled nuclear reactor in the aft bomb bay, with a four-ton lead disc shield installed in the middle of the aircraft between the 1,000-kilowatt reactor and the cockpit. A number of large air intake and exhaust holes were installed in the sides and bottom of the aircraft's rear fuselage to cool the reactor in flight.[38] On the ground, a crane would be utilized to remove the 35,000 pound reactor from the aircraft. To protect the crew, the highly-modified cockpit was encased in lead and rubber, with a 1-foot-thick (30 cm) leaded glass windshield.[38] The reactor was operational but did not power the aircraft; its sole purpose was to investigate the effect of radiation on aircraft systems. Between 1955 and 1957, the NB-36H completed 47 test flights and 215 hours of flight time, during 89 of which the reactor was critical.

Other experiments involved providing the B-36 with its own fighter defense in the form of parasite aircraft carried partially or wholly in a bomb bay. One parasite aircraft was the rather miniscule McDonnell XF-85 Goblin, which docked using a trapeze system. The concept was tested successfully using a B-29 carrier, but docking proved difficult even for experienced test pilots. Moreover, the XF-85 was seen as no match for contemporary foreign powers' newly-developed interceptor aircraft in development and in service, consequently, the project was cancelled.[39]

More successful was the FICON project, involving a modified B-36—called a GRB-36D "mothership"—and the RF-84K, a fighter modified for reconnaissance, in a bomb bay. The GRB-36D would ferry the RF-84K to the vicinity of the objective, whereupon the RF-84K would disconnect and begin its mission. Ten GRB-36Ds and 25 RF-84Ks were built and saw limited service in 1955-1956.

Projects TIP TOW and Tom-Tom involved docking F-84s to the wingtips of B-29s and B-36s. The hope was that the increased aspect ratio of the combined aircraft would result in a greater range. Project TIP TOW was canceled when the combination of two EF-84Ds and a specially modified test EB-29A crashed, killing everyone on all three aircraft. This accident was attributed to one of the EF-84Ds flipping over onto the wing of the EB-29A. Project Tom-Tom, involving RF-84Fs and a GRB-36D from the FICON project (redesignated JRB-36F), continued for a few months after this crash, but was also canceled due to the violent turbulence induced by the wingtip vortices of the B-36.[40]

Strategic Reconnaissance

One of the SAC's initial missions was to plan strategic aerial reconnaissance on a global scale. The first efforts were in photo-reconnaissance and mapping. Along with the photo-reconnaissance mission, a small electronic intelligence (ELINT) cadre was operating. Weather reconnaissance was part of the effort, as was Long Range Detection, the search for Soviet atomic explosions. In the late 1940s, strategic intelligence on Soviet capabilities and intentions was scarce. Before the development of the Lockheed U-2 high altitude spy plane and orbital reconnaissance satellites, technology and politics limited American reconnaissance efforts to the borders, and not the heartland, of the Soviet Union.[42]

One of the essential criteria of the early postwar reconnaissance aircraft was the ability to cruise above 40,000 ft, a level determined by knowledge of the capability of Russian air defense radar. The main Russian air defense radar in the 1950s was the American supplied SCR-270, or locally made copies, which were only effective up to 40,000 ft – in theory, an aircraft cruising above this level would remain undetected.[43]

The first aircraft, which put this theory to the test, was the RB-36D specialized photographic-reconnaissance version of the B-36D. It was outwardly identical to the standard B-36D, but carried a crew of 22 rather than 15, the additional crew members being needed to operate and maintain the photographic reconnaissance equipment that was carried. The forward bomb bay in the bomber was replaced by a pressurized manned compartment that was filled with fourteen cameras. This compartment included a small darkroom where a photo technician could develop the film. The second bomb bay contained up to 80 T-86 photo flash bombs, while the third bay could carry an extra 3,000 gallon droppable fuel tank. The fourth bomb bay carried ferret ECM equipment. The defensive armament of 16 M-24A-1 20 mm cannons was retained. The extra fuel tanks increased the flight endurance to up to 50 hours. It had an operational ceiling of 50,000 ft. Later, a lightweight version of this aircraft, the RB-36-III, could even reach 58,000 ft. RB-36s were distinguished by the bright aluminium finish of the camera compartment (contrasting with the dull magnesium of the rest of the fuselage) and by a series of radar domes under the aft fuselage, varying in number and placement. When developed, it was the only American aircraft having enough range to fly over the Eurasian land mass from bases in the United States, and size enough to carry the bulky high resolution cameras of the day.[44]

The standard RB-36D carried up to 23 cameras, primarily K-17C, K-22A, K-38, and K-40 cameras. A special 240-foot focal length camera was tested on 44-92088, the aircraft being redesignated ERB-36D. The long focal length was achieved by using a two-mirror reflection system. The camera was supposedly capable of resolving a golf ball at an altitude of 40,000 ft. This camera is now with the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright Patterson AFB.[44]

The first RB-36D (44-92088) made its initial flight on 18 December 1949, only six months after the first B-36D had flown. It initially flew without the turbojets. The 28th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing based at Rapid City AFB (later renamed Ellsworth AFB), South Dakota received its first RB-36D on 3 June 1950. Due to severe materiel shortages, the new RB-36Ds did not become operationally ready until June 1951. The 24th and last RB-36D was delivered in May 1951. A total of 24 RB-36Ds were built. Some RB-36Ds were later modified to the featherweight configuration, in which all but the tail guns were removed. The crew was reduced from 22 to 19. These aircraft were redesignated as RB-36D-III. Modifications were carried out by Convair from February 1954 to November 1954.[44]

In 1951 RB-36Ds, with a range of 9,300 miles, began probing the boundaries of the Soviet Arctic and were rather disturbed to find their on-board equipment indicating that they had been detected by Soviet radar - so much for the theory. However, detecting aircraft on ground-based radar was one thing, intercepting them was far more difficult. A number of overflights of Soviet bases in the arctic, particularly the new nuclear weapons test complex at Novaya Zemlya, were made by RB-36 aircraft operating from RAF Sculthorpe in England. RB-36s performed a number of rarely acknowledged reconnaissance missions and is suspected of having carried out numerous penetrations of Chinese (and Soviet) airspace under the direction of General Curtis LeMay.[43]

In early 1950, Convair began conversion of the B-36As to the reconnaissance configuration. Included in the conversions was the sole YB-36 (42-13571). These converted examples were all redesignated RB-36E. The six R-4360-25 engines were replaced by six R-4360-41s. They were also equipped with the four J-47 jet engines that were fitted to the RB-36D. Its normal crew was 22, which included five gunners to man the 16 M-24A-1 20 mm cannon. The last conversion was completed in July 1951. Later, the USAF also bought 73 long-range reconnaissance versions of the B-36H under the designation RB-36H. 23 were accepted during the first six months of 1952, the last were delivered by September 1953. More than a third of all B-36 models were reconnaissance models.[44]

Advances in Soviet air defense systems meant that the RB-36 became limited to flying outside of the borders of the Soviet Union, as well as Eastern Europe. By the mid 1950s, the jet-powered Boeing RB-47E was able to pierce Soviet airspace and conduct a variety of spectacular overflights of the Soviet Union. Some of these flights probed deep into the heart of the Soviet Union, taking a photographic and radar recording of the route attacking SAC bombers would follow to reach their targets. The risks involved in mounting these dangerous sorties over some of the most inhospitable terrain on earth speaks volumes for the courage and skill of the crews involved. Flights which involved penetrating mainland Russia were termed SENSINT (Sensitive Intelligence) missions. One RB-47 even managed to fly 450 miles inland and photograph the city of Igarka in Siberia.[43]

As with the strategic bombardment versions of the B-36, the RB-36s were phased out of the SAC inventory beginning in 1956, the last being sent to Davis-Monthan in January 1959.

Obsolescence

With the appearance of the Soviet MiG-15 in combat over the skies of North Korea in 1950, the propeller-driven bombers in the USAF inventory were simply rendered obsolete as strategic offensive weapons. Although the MiG-15 had deficiencies in range and a lack of radar, the swept-wing Soviet jet could fly faster, higher and attack the propeller-driven B-29s over the skies of North Korea during daylight seemingly with almost impunity with heavy-caliber weapons. It also easily outperformed the F-80C and F-84G straight-winged jet fighter escorts of the B-29. The MiG interceptor forced the United States to switch to night B-29 bombing raids.

The B-36, along with the B-29/B-50 Superfortresses in the USAF inventory in the early 1950s, were all designed during World War II, prior to the jet age. It would take a new generation of swept-wing jet bombers, being able to fly higher and faster to effectively defeat the defense of the MiG-15 or subsequent Soviet-designed interceptors if the Cold War escalated into an armed conflict between the United States and Soviet Union.

With the end of fighting in Korea, President Eisenhower, who had taken office in January 1953, called for a "new look" at national defense. His administration chose to invest in the Air Force, especially Strategic Air Command. The Air Force retired nearly all of its B-29/B-50s to be replaced by the new Boeing B-47 Stratojet. By 1955 the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress swept-wing strategic jet bombers would be entering the inventory in substantial numbers, and the B-36s began to be replaced.

In addition to the obsolescence of the aircraft, other factors leading to the phaseout of the B-36 were:

- The Peacemaker was not designed for aerial refueling, and required intermediate refueling bases in order to reach its planned targets deep in the Soviet Union.

- Its slow speed made it vulnerable to Soviet jet interceptor aircraft, making long-range bombardment flights over Soviet territory extremely hazardous, seriously compromising its ability to reach its planned target and return.

- Radar-guided surface-to air missiles, such as the Soviet SA-2 Guideline, capable of reaching 65,600 ft (20,000 m), emerged.

- The B-36 airframe, especially the wings, proved vulnerable to metal fatigue.

- Inflight wing flexing led to fuel leakage, a common problem.

The scrapping of B-36s began in February 1956. Once replaced by B-52s, they were flown directly from operational squadrons to Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona, where the Mar-Pak Corporation handled their reclamation and destruction. However, defense cutbacks in FY 1958 compelled the B-52 procurement process to be stretched out and the B-36 service life to be extended. The B-36s remaining in service were supported with components scavenged from planes sent to Davis-Monthan for scrapping. Further update work was undertaken by Convair at San Diego (Specialized Aircraft Maintenance, SAM-SAC) until 1957 to extend the life and capabilities of the B-36s. By December 1958, only 22 B-36s (all of them B-36Js) were still operational.[44]

On 12 February 1959, the last B-36J (and the final J built by Convair-52-2827) left Biggs AFB, Texas, where it had been on duty with the 95th Heavy Bombardment Wing, and was flown to Amon Carter Field in Fort Worth, where it was put on permanent display. Within two years, all but five B-36s (which had been saved for museum display) had been scrapped at Davis-Monthan AFB.[44]

Variants

| Variant | Built |

|---|---|

| XB-36 | 1 |

| YB-36 | 1 |

| B-36A | 22 |

| XC-99 | 1 |

| B-36B | 62 |

| B-36D | 26 |

| RB-36D | 24 |

| B-36F | 34 |

| RB-36F | 24 |

| B-36H | 83 |

| RB-36H | 73 |

| B-36J | 33 |

| YB-60 | 2 |

| Total | 385[45] |

- XB-36

- Prototype powered by six 3,000 hp (2,200 kW) R-4360-25 engines and unarmed, one built.

- YB-36

- Prototype, s/n 42-13571,[46] with modified nose and raised cockpit roof, one built later converted to YB-36A.

- YB-36A

- Former YB-36 with modified four-wheel landing gear, later modified as a RB-36E.

- B-36A

- Production variant, unarmed, used for training, 22 built, all but one converted to RB-36E.

- XC-99

- A cargo/transport version of the B-36. Only one sole example was ever produced.

- B-36B

- Armed production variant with six 3,500 hp (2,600 kW) R-4360-41 engines, 73 built, later conversions to RB-36D and B-36D.

- RB-36B

- Designation for 39 B-36Bs temporary fitted with a camera installation.

- YB-36C

- Projected variant of the B-36B with six 4,300 hp (3,200 kW) R-4360-51 engines driving tractor propellers, not built.

- B-36C

- Production version of the YB-36, completed as B-36Bs.

- B-36D

- Same as B-36B but fitted with four J47-GE-19 engines, two each in two underwing pods, 22 built and 64 conversions from B-36B.

- RB-36D

- Strategic reconnaissance variant with two bomb bays fitted with camera installation, 17 built and seven conversions from B-36B.

- GRB-36D

- Same as RB-36D but modified to carry a GRF-84F Thunderstreak on a ventral trapeze as part of the FICON program, 10 modified.

- RB-36E

- The YB-36A and 21 B-36As converted to RB-36D standards.

- B-36F

- Same as B-36D but fitted with six 3,800 hp (2,800 kW) R-4360-53 engines and four J47-GE-19 engines, 34 built.

- RB-36F

- Strategic reconnaissance variant of the B-36F with additional fuels capacity, 24 built.

- YB-36G

- See YB-60.

- B-36H

- Same as B-36F with improved cockpit and equipment changes, 83 built.

- NB-36H

- One B-36H fitted with a nuclear reactor installation for trials, had a revised cockpit and raised nose. This was intended to evolve into the Convair X-6.

- RB-36H

- Strategic reconnaissance variant of the B-36H, 73 built.

- B-36J

- High altitude variant with strengthened landing gear, increased fuel capacity, armament reduced to tail guns only and reduced crew, 33 built.

- YB-60

- Originally designated the YB-36G, s/n 49-2676 and 49-2684.[47] Project for a jet-powered swept wing variant. Due to the difference from a standard B-36 it was re-designated the YB-60.

Related models

In 1951, the USAF asked Convair to build a prototype of an all-jet variant of the B-36. Convair complied by replacing the wings on a B-36F with swept wings, from which were suspended eight Pratt & Whitney XJ57-P-3 jet engines. The result was the B-36G, later renamed the Convair YB-60. The YB-60 was deemed inferior to Boeing's YB-52, and the project was terminated.[48]

Just as the C-97 was the transport variant of the B-50, the B-36 was the basis for the Convair XC-99, a double-decked military cargo plane that was the largest piston engined, land-based aircraft ever built, and the longest practical aircraft (185 ft/56 m) of its era. The sole example built was extensively employed for nearly a decade, especially for cross-country cargo flights during the Korean War. In 2005, this XC-99 was dismantled in anticipation of its being moved from the former Kelly Air Force Base, now the Kelly Field Annex of Lackland AFB in San Antonio, Texas, where it had been retired since 1957. The XC-99 was subsequently relocated to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio for restoration, with C-5 Galaxy transports carrying pieces of the XC-99 to Wright-Patterson as space and schedule permitted.[49]

A commercial airliner derived from the XC-99, the Convair Model 37, never left the drawing board. It would have been the first "jumbo" airliner.[3]

Operators

- 5th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, January 1951–September 1958, Fairfield-Suisun AFB (later renamed Travis AFB), California (also RB-36)

- 6th Bombardment Wing, August 1952–August 1957, Walker AFB, New Mexico

- 7th Bombardment Wing, June 1948-May 1958, Carswell AFB, Texas

- 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, May 1949–April 1950, Fairfield-Suisun AFB (later renamed Travis AFB), California (also RB-36)

- 11th Bombardment Wing, December 1948–December 1957, Carswell AFB, Texas

- 28th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, July 1949–May 1957, Ellsworth AFB, South Dakota (also RB-36)

- 42d Bombardment Wing, April 1953–September 1956, Loring AFB, Maine

- 72d Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, October 1952–January 1959, Ramey AFB, Puerto Rico (also RB-36)

- 92d Bombardment Wing, July 1951–March 1956, Fairchild AFB, Washington

- 95th Bombardment Wing, August 1953–February 1959, Biggs AFB, Texas

- 99th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, August 1951–September 1956, Fairchild AFB, Washington (also RB-36)

Survivors

Only four (and a half) B-36 type aircraft survive today, from the 384 produced.[51]

- YB-36/RB-36E AF Serial No. 42-13571. This was the first prototype to be converted to the bubble canopy used on production B-36s. It was on display in the 1950s and 1960s at the former site of the Air Force Museum, now the National Museum of the United States Air Force, at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio. When the museum's current location at Wright-Patterson was being developed in the late 1950s, the cost of moving the bomber was more than simply flying a different B-36 to the new location and the aircraft was slated to be scrapped. It was cut up at the old museum site by the summer of 1972. Instead, private collector Walter Soplata bought it and transported the pieces by truck to his farm in Newbury, Ohio, where it sits today in several large pieces. The bomb bay currently contains a complete P-47N still packed in its original shipping crate.

- RB-36H-30-CF AF Serial No. 51-13730, is on display at the Castle Air Museum at the former Castle Air Force Base in Atwater, California.

- B-36J-1-CF AF Serial No. 52-2217, is on display at the Strategic Air and Space Museum, formerly located at Offutt Air Force Base, and now just off base near Ashland, Nebraska.[52]

- B-36J-1-CF AF Serial No. 52-2220, is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, (formerly The U.S. Air Force Museum) at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio. Its flight to the museum from Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona on 30 April 1959 was the last flight of a B-36. This B-36J replaced the former Air Force Museum's original YB-36 AF Serial Number 42-13571 (see above). This was also the first aircraft to be placed in the Museum's new display hangar, and was not moved again until relocated to the Museum's latest addition in 2003. It is displayed alongside the only surviving example of the massive 9 ft (2.7 m) XB-36 wheel and tire.

- B-36J-10-CF, AF Serial No. 52-2827, the final B-36 built, named "The City of Fort Worth", was loaned to the city of Fort Worth, Texas on 12 February 1959. It sat on the field at the Greater Southwest International Airport until that property was redeveloped as a business park. It then moved to the short-lived Southwest Aero Museum, which was located between the former Carswell Air Force Base (now NAS Fort Worth) and the former General Dynamics (now Lockheed Martin) assembly plant. From there it went to the Lockheed Martin plant, where some restoration took place. As Lockheed Martin had no place to display the finished aircraft, and local community efforts in Fort Worth to build a facility to house and maintain the massive aircraft fell short, the USAF Museum retook possession of the aircraft and it was transported to Tucson, Arizona for loan to the Pima Air & Space Museum. It is now restored and reassembled at the Pima Air & Space Museum, just south of Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona and is displayed at that location.

Also related is the sole example of the Convair XC-99 cargo version which is undergoing restoration and reassembly at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.

Notable incidents and accidents

Though the B-36 had a better than average overall safety record, 10 B-36s crashed between 1949 and 1954 (three B-36Bs, three B-36Ds, and four B-36Hs). Goleta Air and Space Museum maintains a web site with photographs and lengthy excerpts from the official crash reports.[53] A total of 32 B-36s were written-off in accidents between 1949 and 1957 of 385 built.[54] When a crash occurred, the magnesium-rich airframe burned readily.[55]

B-36s were involved in two "Broken Arrow" incidents. On February 13, 1950, a B-36, serial number 44-92075, crashed in an unpopulated region of British Columbia, resulting in the first loss of an American atom bomb (see 1950 British Columbia B-36 crash). The bomb's plutonium core was dummy lead, but it did have TNT, and it detonated over the ocean prior to the crew bailing out.[56] Locating the crash site took some effort.[57] Later in 1954, the airframe, stripped of sensitive material, was substantially destroyed (in situ) by a U.S. military recovery team.

On 22 May 1957, a B-36 accidentally dropped a Mark-17 hydrogen bomb on a deserted area while landing at Kirtland AFB in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Only the conventional trigger detonated, the bomb being unarmed. These incidents were classified for decades. See list of military nuclear accidents.[53][58]

Specifications (B-36J-III)

General characteristics

- Crew: 9

- Length: 161 ft 1 in [59] (49.40 m)

- Wingspan: 230 ft 0 in (70.20 m [59])

- Height: 46 ft 9 in (14.25 m)

- Wing area: 4,772 ft² (443.3 m²)

- Airfoil: NACA 63(420)-422 root, NACA 63(420)-517 tip

- Empty weight: 171,035 lb (77,580 kg)

- Loaded weight: 266,100 lb (120,700 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 410,000 lb (190,000 kg)

- Powerplant:

- 4× General Electric J47 turbojets, 5,200 lbf (23 kN) each

- 6× Pratt & Whitney R-4360-53 "Wasp Major" radials, 3,800 hp (2,500 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 411 mph [59] (365 knots, 681 km/h [59]) with jets on

- Cruise speed: 230 mph (200 kn, 380 km/h) with jets off

- Range: 6,795 mi (5,905 nmi, 10,945 km) with 10,000 lb (4,535 kg) payload

- Ferry range: 10,000 mi (8,700 nmi, 16,000 km)

- Service ceiling: 48,000 ft (15,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,920 ft/min (9.75 m/s)

- Wing loading: 55.76 lb/ft² (272.3 kg/m²)

- Power/mass (prop): 0.086 hp/lb (120 W/kg)

- Thrust/weight (jet): 0.078

Armament

- Guns: 8 remotely operated turrets of 2× 20 mm (0.787 in) M24A1 autocannons

- Bombs: 86,000 lb (39,000 kg) with weight restrictions, 72,000 lb (32,700 kg) normal

Notable appearances in media

In 1949, the B-36 was featured in the documentary film, Target: Peace, which was centered around the operations of the 7th Bombardment Wing at Carswell AFB. Other scenes included B-36 production at the Fort Worth plant.

In 1955, the film Strategic Air Command was released, starring James Stewart and June Allyson with Stewart playing a baseball star and his subsequent service in Strategic Air Command. The flying sequences (and sounds) of the B-36 dominate the film. This film remains as the only full-length film featuring this aircraft. Unfortunately it is not currently available.[60]

The documentary Lost Nuke (2004) chronicles a 2003 Canadian expedition that set out to solve the mystery of the world's first lost nuclear weapon. The team traveled to the remote mountain British Columbia crash site of 44-92075.[61]

Lore

Throughout its time in service, the B-36 was the subject of USAF lore, some apocryphal, some containing a grain of truth.

"If all engines function normally at full power during the pre-takeoff warm-up, the lead flight engineer will sometimes say to the Aircraft Commander (AC), 'six turning and four burning.'" Erratic reliability led to the wisecrack, 'two turning, two burning, two joking, and two smoking, with two engines not accounted for.'"

See also

- B-36 Peacemaker Museum

- B-36B 44-92075

- Convair B-36 variants

- FICON project

- Lycoming R-7755

- Revolt of the Admirals

- Strategic Air Command

- XF-85 Goblin

- "Victory Bomber"

Related development

- Convair YB-60

- Convair XC-99

- Convair Model 37

Comparable aircraft

Related lists

- List of military aircraft of the United States

- List of bomber aircraft

References

- Notes

- ↑ Convair proposed the name "Peacemaker" in a submission to a contest to name the bomber. Although the name "Peacemaker" was not officially adopted, it was commonly used and sources often state or imply the name is "official".[2]

- ↑ Quote attributed to Captain Banda when he was escorting Air Cadet Michael R. Daciek, later Lieutenant Colonel Daciek, on an inside tour of the XC-99 in 1953.

- Citations

- ↑ Knaack 1988, p. 34.

- ↑ "Peacemaker Name Certificate." 7th Bomb Wing B-36 Association. Retrieved: 28 August 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 "Convair XB-36 Factsheet." National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Taylor 1969, p. 465.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Johnson 1978, p. 1.

- ↑ Jacobsen and Wagner 1980, p. 4.

- ↑ Winchester 2006, p. 49.

- ↑ Leach 2008, pp. 26–28.

- ↑ Jenkins 2002, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Leach 2008, p. 29.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD): B-36 Peacemaker." globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 5 September 2009.

- ↑ Leach 2008, p. 30.

- ↑ Wagner 1968, p. 142.

- ↑ Yenne 2004, pp. 124–126.

- ↑ Wolk 2003, p. 163.

- ↑ Barlow, Jeffrey G. Revolt of the Admirals: The Fight for Naval Aviation, 1945–1950. Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1994. ISBN 0-16-042094-6.

- ↑ Griswold, Wesley P. "Remember the B-36." Popular Science, September 1961. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ Jacobsen 1974, p. 54.

- ↑ Yenne 2004, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Jacobson and Meyer, The Big Stick.

- ↑ AU/ACSC/166/1998-04 "Standard Aircraft Characteristics: F2H-2 Banshee." history.naval.mil. Retrieved: 28 August 2010.

- ↑ "The Revolt of the Admirals." Air Command and Staff College Air University. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ Yenne 2004, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Shiel 1996, p. 7.

- ↑ Puryear 1981, p. 26.

- ↑ "History: Boeing B-17." boeing.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ "Russia sparks Cold War scramble." BBC News, 9 August 2007. Retrieved: 30 April 2010.

- ↑ "Mark 17." globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ Lockett, Brian. "Summary of Air Force accident report." Goleta Air and Space Museum, air-and-space.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ Leach 2008, p. 32.

- ↑ "The Last B-36 and the people who saved it from destruction." cowtown.net, 1 October 2006. Retrieved: 21 September 2007.

- ↑ Morris, Ted. "Flying the Aluminum and Magnesium Overcast." zianet.com, 2000. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ "Interview with B-36B 44-92075 Co-pilot 1st Lt R.P. Whitfield." mysteriesofcanada.com, 1998. Retrieved: 24 September 2007.

- ↑ "Lt. General James Edmundson on: Flying B-36 and B-47 planes." American Experience: pbs.org, January 1999. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ "B-36 Era and Cold War Aviation Forum." delphiforums.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ "Operation Castle: Report of Commander, Task Group 7.1, p. 24 (extract version)." worf.eh.doe.gov, 1 February 1980. Retrieved: 23 September 2007.

- ↑ Miller and Cripliver 1978, pp. 366, 369.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Baugher, Joe. "Convair NB-36H." USAF Bombers: Convair B-36 Peacemaker: joebaugher.com, 19 September 2000. Retrieved: 14 May 2010. Quote: "

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "McDonnell XP-85/XF-85 Goblin." USAF Fighters: McDonnell XP-85/XF-85 Goblin, www.joebaugher.com, 23 October 1999. Retrieved: 14 May 2010.

- ↑ Lockett, Brian. "Parasite Fighter Programs: Project Tom-Tom." Goleta Air and Space Museum, air-and-space.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ Hall, R. Cargill. "The Truth About Overflights: Military Reconnaissance Missions over Russia Before the U-2." Quarterly Journal of Military History, Spring 1997.

- ↑ Wack, Fred J. The Secret Explorers: Saga of the 46th/72nd Reconnaissance Squadrons. Self-published, 1990.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Jacobsen 1997

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 Baugher, Joe. "Convair B-36 Peacemaker." USAF Bombers via joebaugher.com, 19 September 2000. Retrieved: 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, p. 53.

- ↑ "Convair YB-36 'Peacemaker'." AeroWeb. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ "Convair YB-36G (YB-60) 'Peacemaker'." AeroWeb. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ "YB-60 Factsheet." National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ Hill, 1st Lt Bruce R. Jr. "XC-99 begins piece-by-piece trip to Air Force Museum." 433rd Airlift Wing Public Affairs, 22 April 2004.

- ↑ "B-36 Deployment." strategic-air-command.com. Retrieved: 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Yenne 2004, p. 149.

- ↑ "B-36J Peacemaker". SAC Museum. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Lockett, Brian. "Convair B-36 Crash Reports and Wreck Sites." Goleta Air and Space Museum, air-and-space.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ Jenkins 2002, p. 238.

- ↑ Lockett, Brian. "Synopsis of the Air Force Accident Report for RB-36H, 51-13722."Goleta Air and Space Museum, air-and-space.com, 30 July 2003, Retrieved: 23 September 2007.

- ↑ Pyeatt, Don. "Interview with copilot." cowtown.net, 31 August 1998. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ Ricketts, Bruce. "Broken Arrow, A Lost Nuclear Weapon in Canada". Mysteries of Canada, 11 January 2006. Retrieved: 17 August 2007.

- ↑ Adler, Les. "Albuquerque's Near-Doomsday." Albuquerque Tribune, 20 January 1994. Retrieved: 10 August 2009.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 Grant and Dailey 2007, p. 206.

- ↑ Thomas 1988, p. 166.

- ↑ Jorgenson, Michael, producer. "Lost Nuke". Myth Merchant Films, Spruce Grove, Alberta, 2004.

- ↑ Daciek, Michael R. "Speaking at random about flying and writing: B-36 Peacemaker/Ten Engine Bomber." YourHub.com, 13 December 2006. Retrieved: 6 April 2009.

- Bibliography

- Ford, Daniel. "B-36: Bomber at the Crossroads". Air and Space/Smithsonian, April 1996. Retrieved: 3 February 2007.

- Grant, R.G. and John R. Dailey. Flight: 100 Years of Aviation. Harlow, Essex: DK Adult, 2007. ISBN 978-0756619022.

- Jacobsen, Meyers K. Convair B-36: A Comprehensive History of America's "Big Stick". Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military History, 1997. ISBN 0-7643-0974-9.

- Jacobsen, Meyers K. Convair B-36: A Photo Chronicle. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military History, 1999. ISBN 0-7643-0974-9.

- Jacobsen, Meyers K. "Peacemaker." Airpower, Vol. 4, No. 6. November 1974.

- Jacobsen, Meyers K. and Ray Wagner. B-36 in Action (Aircraft in Action Number 42). Carrollton, TX: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1980. ISBN 0-89747-101-6.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. B-36 Photo Scrapbook. St. Paul, Minnesota: Specialty Press Publishers and Wholesalers, 2003. ISBN 1-58007-075-2.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. Convair B-36 Peacemaker. St. Paul, Minnesota: Specialty Press Publishers and Wholsalers, 1999. ISBN 1-58007-019-1.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. Magnesium Overcast: The Story of the Convair B-36. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2002., ISBN 978-1-58007-129-1.

- Johnsen, Frederick A. Thundering Peacemaker, the B-36 Story in Words and Pictures. Tacoma, WA: Bomber Books, 1978. ISBN 1-55046-310-1.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Post-World War II Bombers, 1945-1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1988. ISBN 0-16-002260-6.

- Leach, Norman S. Broken Arrow: America’s First Lost Nuclear Weapon. Calgary, Alberta: Red Deer Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-88995-348-2.

- Miller, Jay and Roger Cripliver. "B-36: The Ponderous Peacemaker." Aviation Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 4, 1978.

- Morris, Lt. Col. (ret.) and Ted Allan. "Flying the Aluminum and Magnesium Overcast". The collected articles and photographs of Ted A. Morris, ©2000. Retrieved: 4 September 2006.

- Orman, Edward W. "One Thousand on Top: A Gunner's View of Flight from the Scanning Blister of a B-36." Airpower, Vol. 17, No. 2, March 1987.

- Puryear, Edgar. Stars In Flight. Novato, Presidio Press, 1981. ISBN 0-89141-128-3

- Pyeatt, Don. B-36: Saving the Last Peacemaker (Third Edition). Fort Worth, Texas: ProWeb Publishing, 2006. ISBN 0-9677593-2-3.

- Shiel, Walter P. "The B-36 Peacemaker: "There Aren't Programs Like This Anymore". cessnawarbirds.com. Retrieved: 19 July 2009.

- Taylor, John W.R. "Convair B-36." Combat Aircraft of the World from 1909 to the present. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969. ISBN 0-425-03633-2.

- Thomas, Tony. A Wonderful Life: The Films and Career of James Stewart. Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1988. ISBN 0-8065-1081-1.

- Wagner, Ray. American Combat Planes. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1968. ISBN 0-385-04134-9.

- Winchester, Jim. "Convair B-36". Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile). Rochester, Kent, UK: The Grange plc., 2006. ISBN 1-84013-929-3.

- Wolk, Herman S. Fulcrum of Power: Essays on the United States Air Force and National Security. Darby, Pennsylvania: Diane Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-4289-9008-9.

- Yenne, Bill. "Convair B-36 Peacemaker." International Air Power Review, Vol. 13, Summer 2004. London: AirTime Publishing Inc., 2004. ISBN 1-880588-84-6.

External links

- Cowtown.net: Portal to B-36 resources

- Baughers Encyclopedia: B-36 versions

- USAF Museum: XB-36

- USAF Museum: B-36A

- AeroWeb: B-36 versions and survivors

- Aerospaceweb: B-36 technical data

- PBS Online: Lt. Gen. James Edmundson interview transcript: Flying B-36 and B-47 planes. "Race For the Superbomb"

- ZiaNet: B-36 operations Walker AFB Roswell New Mexico 1955-1957

- ZiaNet: B-36 operations Walker AFB Roswell New Mexico 1955-1957

- Story of B-36 Crash in El Paso in 1953

- I Flew Thirty-One Hours In A B-36 September 1950 Popular Mechanics

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||